We all exercise or train to become better versions of ourselves but we don’t always know how to get better. Years of experience in the gym and other training environments have shown that many people exercise, but most don’t do enough to get real results. Exercise and training are there to push your body past limits so that it can adapt to the load, making you physically and psychologically stronger and fitter. However, there is also a chance of doing too much.

There are three main variables you can change to dial in your training to get fitter, stronger, or bigger.

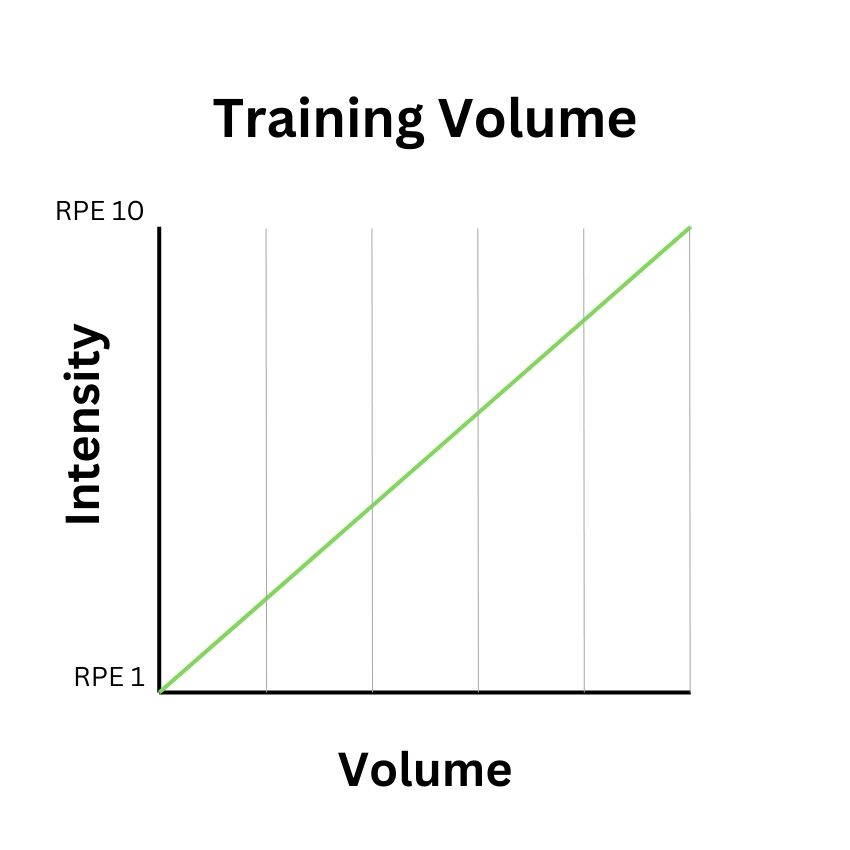

Training volume

Volume is often inaccurately described as the duration of the training, however, it’s the quantity of activity performed during training. “It is the primary component of training because it’s a prerequisite for high technical, tactical, and physical achievement.” (Periodization, T.O. Bompa & G.G. Haff). The specifics of the volume will always depend on the sport or activity. For endurance athletes, the main component measured is the distance covered. Resistance training and weightlifting will measure the accumulative weight lifted during a workout (Volume Load = sets x reps x load in kg).

How can you increase training volume?

- If you’re an endurance athlete work on increasing the distance covered per run or week.

- Each week, try to add an extra rep or two to each set.

- If you are building more capacity, add another full working set to the exercise.

To add volume, you’ll be adding distance, sets, and reps to the workout. Doing a higher volume workout will impact your recovery time between workouts.

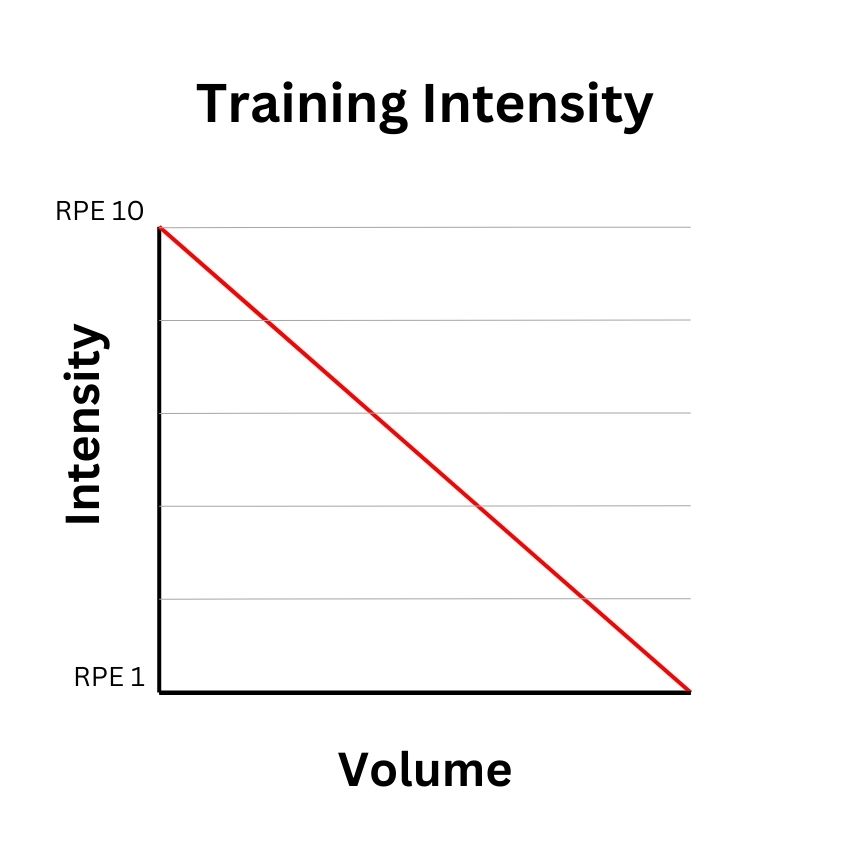

Training Intensity

Where volume is the quantity of work during training, intensity can be seen as the quality of work being done. With relation to resistance training, intensity can be seen as the energy expenditure or work per unit of time. i.e. workout). The more work you do during a workout, the higher the intensity and fatigue accumulated. However, intensity also has a psychological component whereby your ability to handle and overcome mental challenges during a tough workout or training segment.

intensity is measured differently between sports and activities. Endurance athletes will look at average heart rate as they run, cycle, or row. Maximum heart rate will also be used during resistance training but power output will become increasingly important.

There are two easy-to-follow methods of assessing intensity when training.

REP (Rate of perceived exertion)

Training hard is very relative and you need to find your “sweet spot” for training. Each level of RPE is a guide for progression. Each intensity zone has its uses whether you’re training for endurance or weight training.

RPE Scale:

- 1-4: This is where you’ll be warming up. You’ll either be jogging very slowly or doing mobility exercises, getting a light sweat.

- 5-6: The warm-up and speed set intensity. Low intensity and moderate weights that slightly work the muscles to prepare for main activities or work on explosiveness. Endurance athletes will be able to chat but with laboured breathing.

- 7-8: This is your working capacity. You’ll be doing your working strength sets or running but with shortness of breath and talking in short sentences.

- 9: Pushing hard and barely able to maintain the intensity of the exercise. Reps are slowing down and form is becoming worse—barely anything left in the tank.

- 10: You’ve pushed so hard that there is no way you can do another rep. Systemic and muscular failure happens here. Not recommended too often.

While RPE is great for endurance athletes, it can split those doing resistance training. RPE is perfect for powerlifters who work according to their maximal efforts. They tend to work with lower weights at higher intensity.

RIR: Reps in Reserve

If you want to build muscle, you could use the RIR method for your workouts. These are the reps in reserve for each set. It can be tricky to figure out, but so does the RPE scale. The more you use it, the better you’ll get.

You don’t want to start a new training block too heavy, so training each set to about 3 RIR is a good start (this could change in the final set). By adding weight each week, your reps in reserve will decrease and you’ll progressively get stronger.

Ways of altering intensity:

- Increasing the speed over time or quickness of a specific exercise. E.g. running faster

- Increase the weight lifted for an exercise.

- Decreasing rest times between sets and exercises.

- Performing endurance, interval, and tactical exercises at a higher % of maximal heart rate.

- Have more intense training weeks before adding a deload week as part of a training block. E.g. 3;1 block to 4:1 training block.

Training Density

Training density is going to involve how often you’re training. The frequency of your workouts will depend on your training intensity and your recovery. If you’re recovering long before the next workout, you might consider adding another workout to your week. However, depending on your goals and program, increasing training frequency will look different to somebody else.

How to adjust training density:

- If your muscles recover a few days before the next workout, adding another workout for that muscle group could improve adaptation. E.g. Training legs 2-3 times a week instead of once.

- Have more speed sessions or longer runs during the week if you’re an endurance or track athlete.

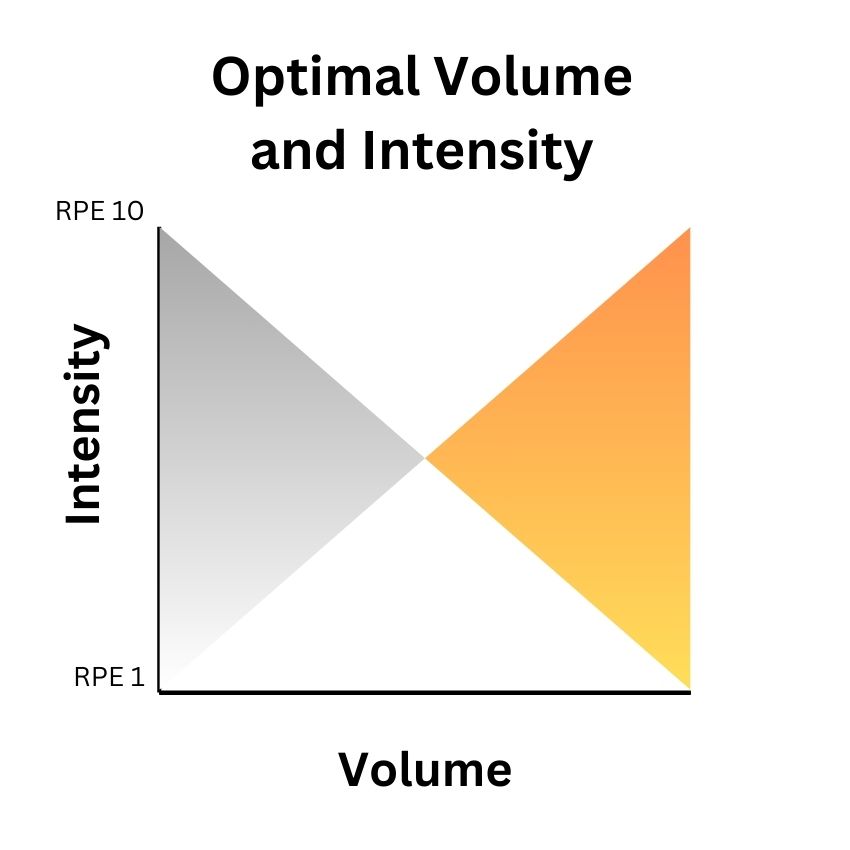

Relationship between Volume and Intensity

There is a trade-off between volume and intensity. You can add all of the reps and sets you want, but it will impact how heavy you can load the bar. You can also run far but you won’t be running as fast as possible.

Optimal Volume and Intensity

If you’re building muscle, you will be adding loads of sets and reps to your workout to stimulate muscle growth, but you won’t be training very heavily. If you’re training for strength, your reps will be lower, rest times longer but the weight will be much heavier. You want to find the perfect zone for your specific goals.

There is no special variation that suits everybody, which is why well-planned programs make such a big difference.

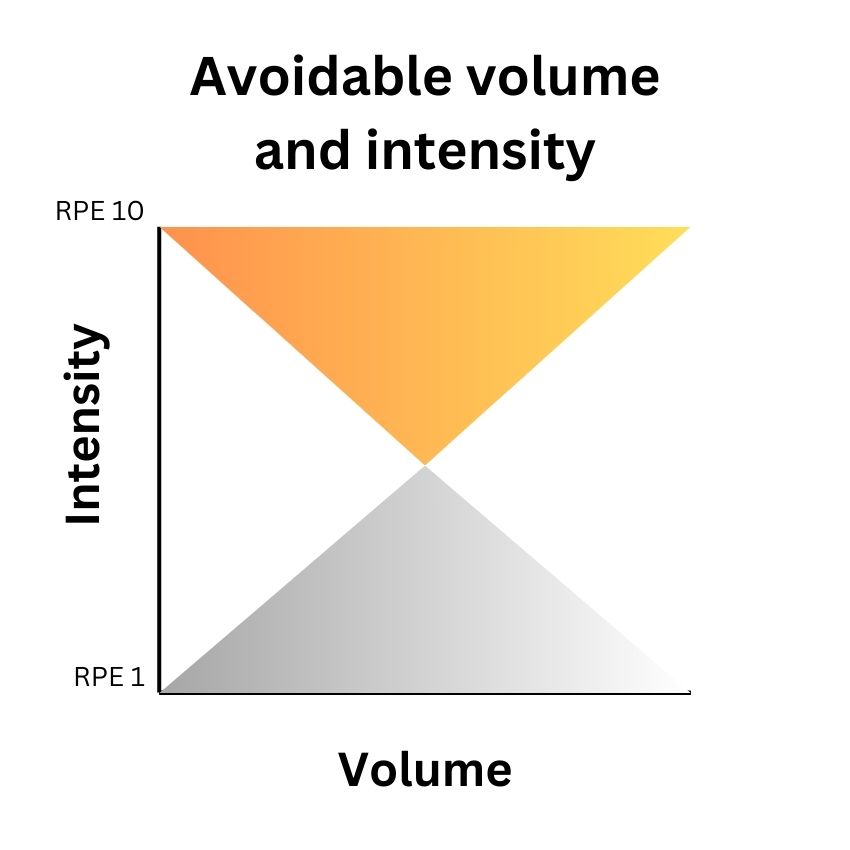

Avoidable Volume and Intensity

There are two more scenarios that you don’t want to find yourself in. These are often determined by no training plan, trying to follow elite athlete intensity, or being unable to train very hard.

You’ve got the group who often starts too heavy, always trains to failure and ego lifts with way too much weight on the bar. They load the intensity and increase the volume so much that they’re sore for a week, train with a sub-optimal range of motion, and increase the risk of injury. This approach can also lead to overtraining.

The second group is often the beginners. They are unsure how to train effectively and/or worry about injury or muscle growth way too much. Unfortunately, this is also the zone, where for most of history, women were told to train because otherwise they’ll get bulky. This group of individuals exercise, but not hard enough to make any gains or they get them very slowly.

These two scenarios are avoidable because they’re quite easy to fix with correct education and programming.

Final Thoughts

Understanding the relationship between volume, intensity, and density can help you make those gains you want so much. You want to train hard and often enough to stimulate your muscles and nervous system but not so hard that you get hurt. You also want to ensure that you’re doing exercise at a high enough volume and intensity to make any gains at all.

These variables are changeable for the individual and individual goals, so take the time to learn and enjoy the process of getting fitter and stronger.

Written by Gary Dunn a.k.a. @geekphysique_za